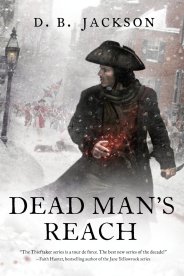

David B. Coe won the William L. Crawford Memorial Award for best new fantasy author for his The LonTobyn Chronicles back in 1999. Since then he’s gone on to publish the Winds of the Forelands and Blood of the Southlands fantasy series with Tor Books, the Case Files of Justis Fearsson (SPELL BLIND, HIS FATHER’S EYES and SHADOW’S BLADE) with Baen Books and his Thieftaker historical fantasy series described as “Sam Adams meets the Dresden Files” under the pseudonym D.B. Jackson (also Tor). Kirkus Reviews calls his work “innovative and engaging” as well as “thoroughly engrossing”. His work has also been called “amazing” (Kat Richardson), “evocative and captivating” (AuthorLink) and “a tour de force” (Faith Hunter). I could, of course, go on and on.

David and I have worked together for lo these many years, and he’s recently come full circle with his very first novel, CHILDREN OF AMARID, just reissued and the sequels, THE OUTLANDERS and EAGLE-SAGE also in the works. Thus, I asked him, as a veteran of the industry, what he’s learned between then and now, and he’s here to share his insight!

__________

I have recently edited and reissued my very first novel, Children of Amarid, the opening volume in my LonTobyn Chronicle. I call this reissue the Author’s Edit (like the Director’s Cut of a movie) because I took the opportunity to fix many of the first-novel flaws I saw in the book and have wanted to edit out since its publication. It’s not that the book as originally written was bad. Children of Amarid established me commercially and critically, and the series won me the Crawford Fantasy Award. But still, those rookie mistakes bugged me; fixing them has been great fun, not to mention satisfying. The Author’s Edits of the second and third books, The Outlanders and Eagle-Sage, will be released in October and December.

I have recently edited and reissued my very first novel, Children of Amarid, the opening volume in my LonTobyn Chronicle. I call this reissue the Author’s Edit (like the Director’s Cut of a movie) because I took the opportunity to fix many of the first-novel flaws I saw in the book and have wanted to edit out since its publication. It’s not that the book as originally written was bad. Children of Amarid established me commercially and critically, and the series won me the Crawford Fantasy Award. But still, those rookie mistakes bugged me; fixing them has been great fun, not to mention satisfying. The Author’s Edits of the second and third books, The Outlanders and Eagle-Sage, will be released in October and December.

Children of Amarid was first published in 1997, which is a really, really long time ago. The person who wrote that book must be, you know, old. Not “Rime-of-the-Ancient-Mariner” old, but at least venerable. Perhaps even vintage. Certainly grizzled.

I’m not sure I was ever the Hot New Thing in Fantasy, but if I was, I’m definitely not anymore, and haven’t been for a while. On the other hand, at this point I’m a Survivor, someone who’s Been Around Forever and Seen It All. And I suppose that’s kind of cool.

The fact is, I have seen a lot. The publishing industry isn’t known for being particularly quick to change, and yet over the course of my career I’ve seen remarkable transformations touching on everything from stylistic norms of writing, to genre and subgenre categories, to the way books are sold and read.

I started writing Children of Amarid in 1993 and sold the novel to Tor Books in the spring of 1994, based on five chapters and an outline. (Because the book wasn’t finished, needed a good deal of editing, and then had to be slotted into Tor’s publication schedule, it took another three years for it to be published.) I bring up these dates because 1993 and 1994 were significant years in publishing in general and speculative fiction in particular.

But let me back up just a bit. When I first published my LonTobyn books, I did what every writer would do automatically today: I created a website. The thing is, when I did it websites were a big deal. I would tell people I was a writer and would get in response the 1990s version of “Meh.” But when I then added that I had my own website, people would be, like, “Oooohhhh! You have a website?!” As if I’d said, “I have a unicorn.” But already the world was changing. In 1994, as I was signing my contract with Tor and finishing my book, some guy out in Seattle was starting an online bookstore unlike any we’d seen before. The guy’s name was Jeff Bezos, and he called his store Amazon.

The LonTobyn Chronicle is alternate world epic fantasy, because back in 1993 when I started it, that’s what I loved to read and that’s what I assumed people meant when they talked about “fantasy.” But that same year a book came out that would change “fantasy” forever, and would influence profoundly the course of my writing career. Laurell K. Hamilton’s Guilty Pleasures, the first of her Anita Blake, Vampire Hunter novels, ushered in a new trend in speculative fiction, introducing readers to what we now think of as urban fantasy. Hamilton’s books combined horror, noir detective stories, and romance in a way that made possible the novels of Kim Harrison, Jim Butcher, Faith Hunter, Patricia Briggs, and so many others, including my Thieftaker Chronicles, a historical urban fantasy series that I write as D.B. Jackson, and my Case Files of Justis Fearsson, a contemporary urban fantasy that I write under my own name.

What about those stylistic changes I mentioned? When I got into the business, editors and writers were just moving away from two things that authors used a ton in the 70s and 80s and use very little now: omniscient point of view and said bookisms. The former is a narrative voice in which the author gives readers access to the thoughts and emotions of several characters at a time, something we now refer to, and not kindly, as head-hopping. Said bookisms are those words we use in dialog attribution instead of “said” or “asked.” “He opined,” “she growled,” “he hissed,” “she inquired,” etc. Again, in today’s market, these are considered a sign of poor writing, of “telling” rather than “showing.” Looking through books published in the 80s and 90s, you’ll also find far more adverbs than you would in a book published today. Literary style, like car design and clothes fashion, changes over time.

In the early 2000s, bookstores decided that they wanted to fit more books on their shelves and keep book price points at a certain level, and so they told publishers that they preferred shorter novels. My first five novels — the three LonTobyn books and the first two volumes of my Winds of the Forelands series — each came in at over 200,000 words. Now my publisher wanted to know if I could cut the remaining two Forelands books in half. I couldn’t, but I was able to find a way to turn the two remaining novels in the series into three somewhat shorter books. My Blood of the Southlands books came in at 140,000 words. My Thieftaker and Fearsson novels are all between 100,000 and 110,000.

Of course, with the advent of ebooks, book length has become less of an issue. Big books are back in style — ask George R.R. Martin, or Patrick Rothfuss, or any number of others who are writing novels to rival the length of the epic fantasies I remember reading in my twenties. In many respects, digital books have brought on a publishing revolution that goes far beyond book length — widespread self-publishing, e-readers that can hold entire libraries and fit in a pocket, a resurgence in short fiction markets. And yet, in other ways, digital books have had less impact than one might have expected. According to some forecasts made a decade ago, paper books were supposed to be extinct by now. Just like vinyl records . . . Yeah, just like. Instead, they continue to make up more than half of all book sales in the United States. People, it turns out, like to read traditional books. Most readers are hybrids, using ebook readers for convenience, but maintaining a paper library for those books they truly love.

Charting the changes that have overtaken the publishing world in the past twenty years could fill a book of its own — a big one. And this post is already long enough. But I would leave you with a couple of thoughts. Despite the evolution of — and revolution in — publishing that we hear so much about, notwithstanding predictions of doom and gloom for the written word, several essential truths persist: Good stories continue to sell; compelling, well-conceived characters continue to drive every good story; and previously unpublished writers continue to fascinate us with new, exciting characters.

Books can take us everywhere, and with ereaders, we can do the same with them. But the written word isn’t going anywhere. It’s here to stay.

*****

GIVEAWAY!

David is giving away a $25 Amazon or Barnes & Noble gift card (winner’s choice), or one of two copies of CHILDREN OF THE AMARID. Open to US residents only. Click here for the Rafflecopter giveaway!

FOLLOW DAVID!

http://www.davidbcoe.com/blog/

http://www.dbjackson-author.com

I had no idea that omniscient POV stuck around until the early 90s. I wonder if that will ever make a comeback.

LikeLike

Omniscient =/= head-hopping. Head-hopping is when the narrative abruptly switches POV, often without any indication that it’s doing so, and often just as abruptly switching back to the original narrative POV.

Stephen King does it for a sentence or two in Hearts in Atlantis, and for some reason it was never edited out.

Now, I’ll agree there was an anti-head-hopping movement that put a chill on third-person omniscient, but they are not and never were the same thing. That this disinformation continues to circulate is disquieting.

LikeLike

Head-hopping is really any time you know what more than one character is thinking in a scene. Omniscient leaves room for this because there’s no single viewpoint character, and so sometimes the focus switches from one to another, essentially hopping heads.

LikeLike